A Frosty Conquest of the Pole as Part of Finnish Outdoor History

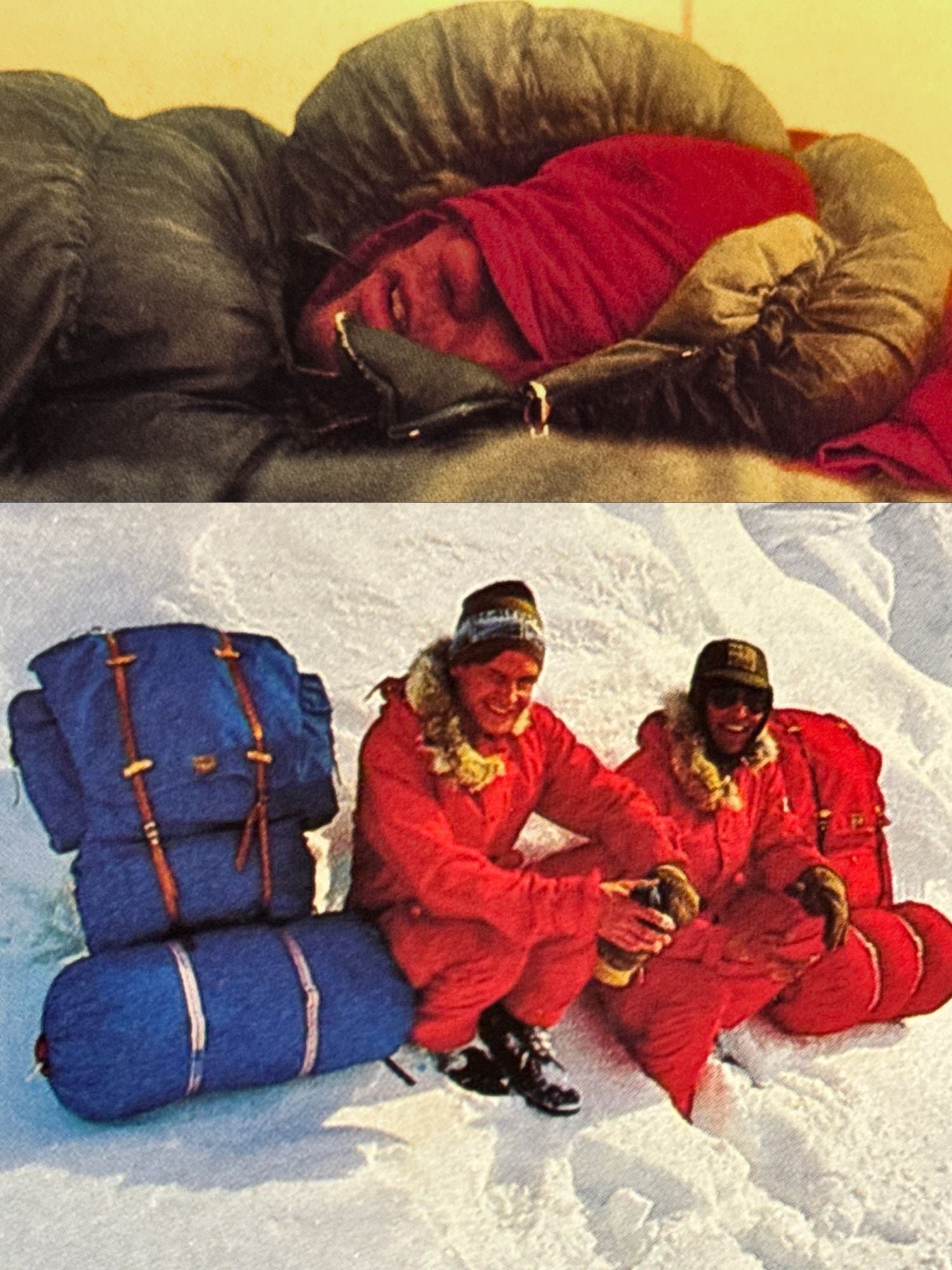

The year 1984 remains etched in the history of outdoor exploration. That year, the eight-member Finnish Huurre expedition skied to the geographic North Pole as only the second team in the world to do so. The expedition travelled on skis, pulling their gear in sledges across pressure ridges and open leads. The achievement was internationally significant and recorded in the Guinness Book of Records.

For decades, polar exploration had been a Norwegian stronghold. The Huurre expedition proved that Finns, too, possessed the Sisu and perseverance required for achievements that write themselves into the history books.

For Halti, the expedition’s equipment partner, the journey marked the beginning of a new era. The polar ice had been traversed for more than a hundred years, but previously explorers had relied on traditional fur, wool, and other natural materials. Now, new technical materials were available, along with growing expertise in meeting the demands imposed by such an expedition. Halti rose to the challenge, and with the conquest of the North Pole, the company’s products and material expertise advanced to a new level.

At the Mercy of the Polar Ice

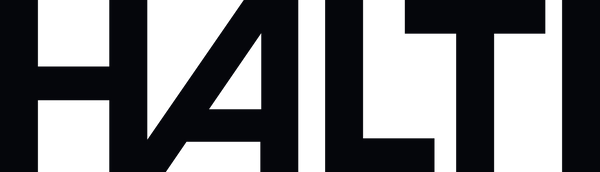

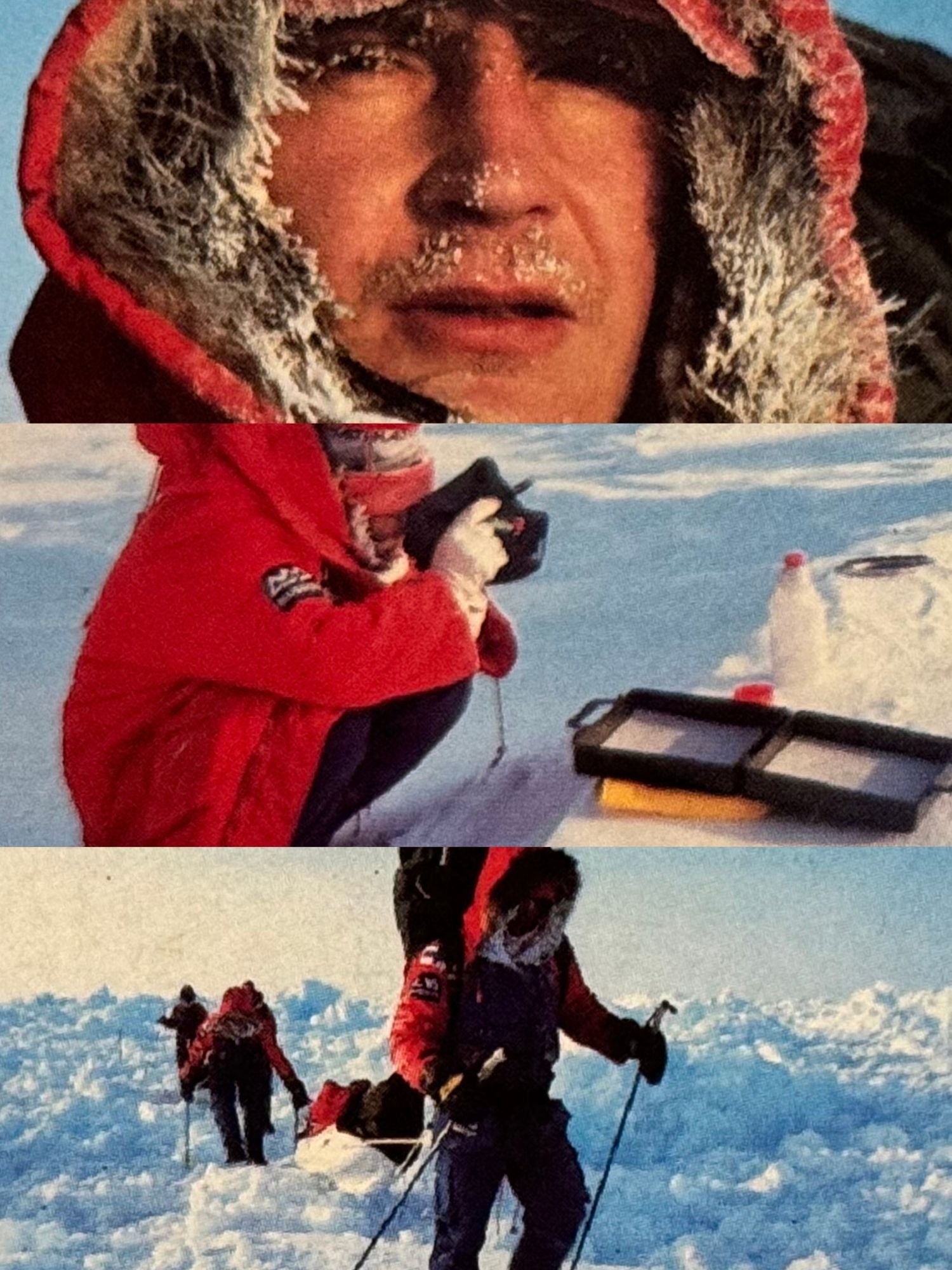

The Arctic Ocean is covered by slowly drifting, multi-year ice. At the North Pole there is nothing permanent, only constantly moving ice above a sea thousands of meters deep. The fractured ice, open leads, and even tower-high ice blocks made progress unpredictable.

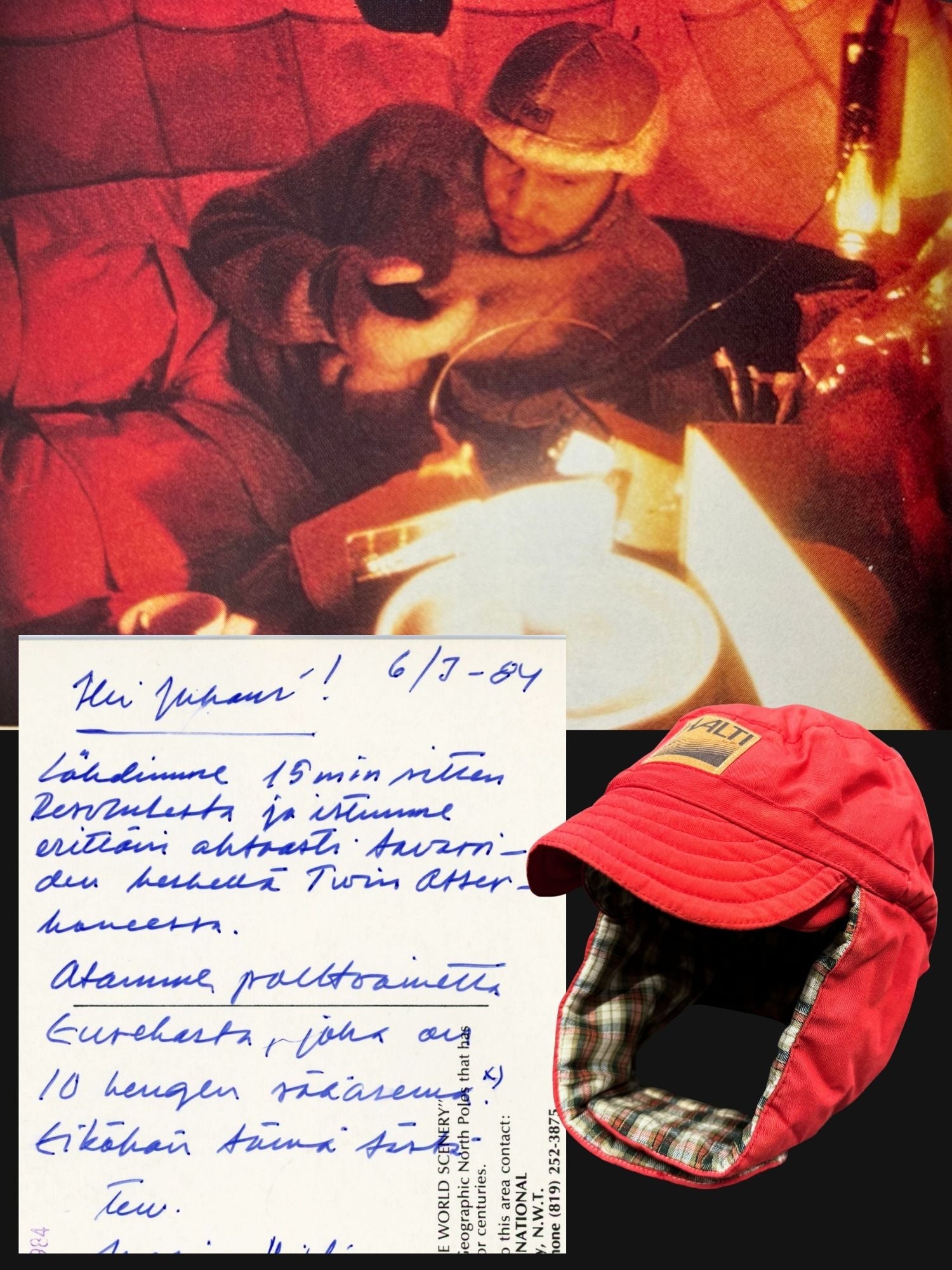

The ski journey began on March 6, 1984, from Ellesmere Island in Canada and lasted a total of 74 days.

The eight-man expedition advanced solely by muscle power, skiing and pulling their sledges. Resupply drops were carried out by air. The movement of the ice could mean that although the team skied 15 kilometers north in a day, the next day they might find themselves several kilometers farther south.

Although the journey took place in spring, temperatures ranged from around –20°C during the day to as low as –50°C at night. The beginning was particularly harsh, for both men and equipment. During the first month, temperatures never rose above –30°C. The wind made the cold biting, and the risk of frostbite was constant. Sudden storms and poor visibility could halt progress completely. Because of pressure ridges, some days’ progress amounted to only a few kilometers, and some days were spent inside the tent while storms raged outside.

The awareness of polar bears in the vicinity added its own tension to camp life.

Years of Preparation

The expedition consisted of adventurous friends, with its core formed by a group of scouts from Oulu. They founded Retkiryhmä 76 as early as 1976, focusing on demanding Arctic treks. The oldest member of the group, Jussi Kauma, served as the driving force behind the project.

The expedition’s name, Huurre, meaning “frost”, came from a sponsor manufacturing refrigeration equipment. Halti was responsible for the gear, and the magazine APU joined early on as a sponsor on the condition that a journalist could participate. Journalist Matti Saari was selected for the role.

The base of operations was in Resolute Bay, an Inuit settlement established in the 1950s in Canada’s Arctic region. From there, the expedition flew for several hours to the starting point at the northern tip of Ellesmere Island. Ahead lay a harsh journey of approximately 1,000 kilometers across drifting ice, pressure ridges, open leads, and icebergs. Progress was slow, and at times the sledges had to be carried.

“In those conditions, you could plan your progress in half-hour segments. Then you would once again face a lead, a pressure ridge, or suddenly changing weather. A whiteout would come, and visibility would disappear completely,” Jussi Kauma recalls.

Dramatic Moments on the Ice and in Finland

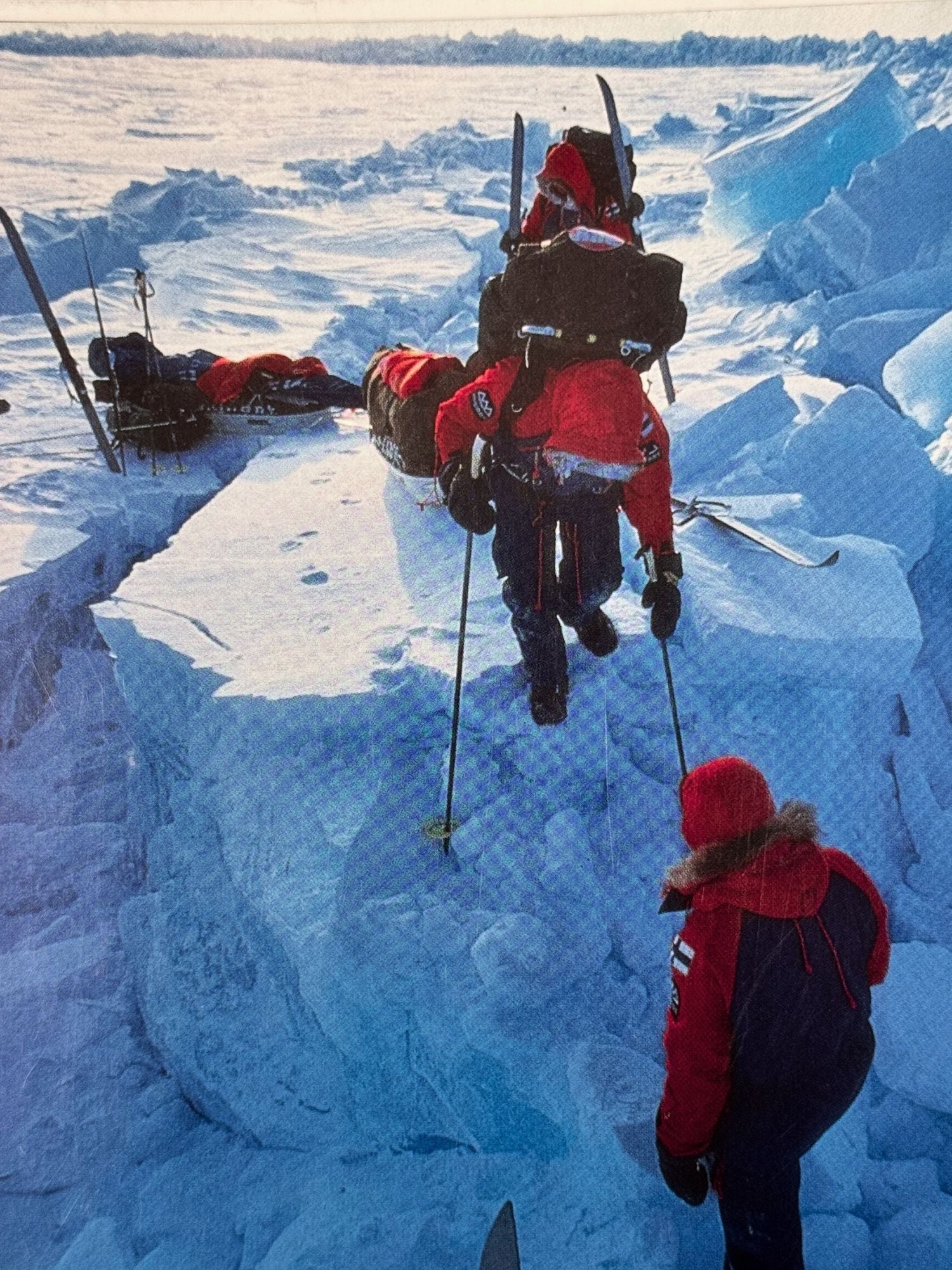

The expedition meant constant physical exertion. Psychologically, the journey was monotonous and isolated from the rest of the world. Days were filled with skiing, maintaining equipment, and resting. Drying gear was laborious. Coffee, chewing gum, and occasional celebrations brought variety to the days.

Communication with the support team was maintained by radio, though connections were not always reliable. In addition, the team used a primitive satellite navigation device the size of a banana crate, which transmitted location data in numeric codes via France and the United States to Canada. The first resupply flight failed, and the supplies dropped at the camp were scattered across the glacier by the wind.

In mid-March, the radio began transmitting a distress signal, triggering preparations for a rescue operation in Canada. In Resolute Bay, it was feared that the group had met with an accident. But in the end, it was merely a communications error. Meanwhile, the expedition was spending a rest day in their tent, completely unaware of the situation.

Back home in Finland, loved ones carried on with their daily lives. News of joyful family events as well as sorrowful tidings were exchanged through letters and phone calls.

The Finnish Flag at the North Pole

The expedition reached the North Pole on Sunday, May 20, 1984. The news was broadcast that same day on Sunnuntai-TV: the Finnish flag had reached the North Pole.

At the site, Jussi Kauma buried an appeal for the protection of the world’s nature in the ice.

Among confirmed visitors to the North Pole, the Huurre expedition was the sixth, and its members became the 56th to 62nd people in history to reach the North Pole under their own power. There were no landmarks or ceremonies, only the fulfillment of a dream. Years of preparation had carried the adventurers safely to their destination. Now they only had to make it safely home.

In Finland, the reception was celebratory. The expedition was widely honored, and the first weeks were filled with events and media attention. Prime Minister Kalevi Sorsa, patron of the expedition, invited the group to dinner. It was the realization of a great dream, not only for the expedition members, but for everyone involved in the project.

Equipment Pushed to the Extreme

Halti’s role as outfitter for the Huurre expedition was no coincidence. The company’s founder, Juhani Hyökyvaara, had a personal passion for developing outdoor equipment. As a young scout, he learned his first lessons at a company called Pylkönmäen Nahkatyö. Later, while working at the sporting goods store Oy Skoha Ab, he worked closely with manufacturers, athletes, and wilderness guides, listening carefully to where equipment performed well and where it failed. Over the years, these insights built deep, user-driven understanding.

When Halti was founded in the early 1970s, its guiding principle was to create products for each sport that were as durable as possible, yet functional and lightweight. Product development played a central role from the very beginning, with the aim of combining field experience with technical expertise.

Retkiryhmä 76 and the Beginning of the Partnership

The first meeting took place at the Riihimäki Outdoor Fair in 1977, when representatives of Retkiryhmä 76, Jussi Kauma and equipment manager Olli-Pekka Nordlund, came to explore the products of the newly founded and trademark-registered Halti. The young adventurers’ initial reaction was skeptical, but their critical tone quickly changed, and soon a handshake sealed the partnership. Retkiryhmä 76 ultimately became an important and long-term partner in Halti’s product development.

Design work for the North Pole expedition gear began in full force in 1980. What was originally envisioned as a smaller project grew over the years into a major financial effort for a small company. In the end, the expedition had more than 900 Halti products at its disposal. Apart from footwear and gloves, all clothing and shelter equipment were supplied by Halti.

The greatest challenges were cold and moisture. Until then, tents and sleeping bags had been made from natural materials. Cotton fabrics and down insulation were heavy and nearly impossible to dry once wet. The North Pole project forced a new way of thinking. Lightness and water repellency became central priorities, leading to the adoption of, for example, synthetic fiber sleeping bags.

Several tent structures were tested before settling on a pyramid design that combined spaciousness, wind resistance, and quick setup. In the development of backpacks and clothing, new lighter solutions were also tested, improving usability and protection.

In addition to field tests, the products and features developed for the Huurre expedition were studied in laboratories in Otaniemi.

The North Pole as a Turning Point

The project’s impact was visible in product innovations across Halti’s collection. The name “Northpole” appeared on clothing and backpacks, and synthetic insulation began its broader breakthrough. Solutions developed together with explorers operating in extreme conditions were applied throughout the collection, raising overall performance to a new level.

The North Pole project crystallized the company’s original philosophy: the best products are born in real use and in the most demanding conditions possible. The collaboration with the expedition made Halti equipment not only functional but reliable. If the products endured at the North Pole, they could be trusted anywhere.

With the wide publicity the expedition received, Halti became associated with products suited for demanding sports and extreme conditions. High quality and credibility earned in practice made the products desirable. The North Pole was not just one expedition, it was a defining moment that shaped Halti’s identity as a credible Finnish pioneer in outdoor equipment design.